The best cigars come from Cuba

Text: Marco Barneveld | Photography: Frits Meyst

Every cigar smoker can agree the very best cigars come from Cuba. Cigars and tobacco are not just a source of income for the island, they are a lifestyle. Welcome to the land where the cigar was born.

It is six o’clock in the morning. The view from our hotel overlooks the Valle de Viñales. A milk-white river of mist flows through the valley. A few palm trees stick out from the fog against a background of limestone hills called mogotes. The sun shines dimly and colours the sky bright-orange. As the mist slowly clears, you see in distance green fields filled with aromatic plants. Welcome to the epicentre of tobacco production. Viñales can easily be called the gateway to where the best tobacco in the world comes from, the province of Pinar del Rio. Its beating heart lies a little further to the west, Vuelta Abajo. Here, according to most cigar purists, Mother Nature provides the very best tobacco grown anywhere in the world, and Cubans roll the most beautiful cigars from it.

The Taíno settled on Cuba around the year 300AD. Originally from the Orinoco Delta in present-day Venezuela, they reached Cuba via Florida and introduced agriculture to the island and grew some crops, including tobacco. These were the natives that Columbus encountered when he first set foot in the New World. The natives had a bunch of leaves in their mouths which they lit so they could inhale the smoke, as Columbus observed. Curiously he would have nothing to do with tobacco himself, even throwing a gift of tobacco from the natives overboard during his first trip.

The name Cohiba comes from the native Taíno. That is how they called the smoking bunch of tobacco leaves

Spanish and other European sailors however soon began to bring cigars back with them. In 1520 a small number of cigars were available in Spanish and Portuguese ports. Their use, a sign of wealth, spread to France and Italy via the French ambassador to Portugal, Jean Nicot. If you’re thinking that name looks familiar, then you’d be right. Nicot gave his name to Nicotine, the element that carries the flavour, like alcohol in wine. In 1560 he sent tobacco to Queen Catherine de Medici to help cure her headaches. Nicotine is not only found in tobacco but also in tomatoes, potatoes and aubergines, all members of the nightshade family. In Britain, it’s possible that Sir Walter Raleigh was responsible for the introduction of tobacco and the new fashion of smoking. The rest is history. The name Cohiba, the most well-known Cuban cigar brand, comes from the Taíno language. The name they gave to the bunch of leaves they held in their mouths.

We stand on a kind of balcony that looks over the tobacco crop of the Hoyo de Mena tobacco plantation in San Juan y Màrtinez. In the fields, workers are busy among the green plants. Laudelina Pozo Leal offers us a hand-rolled cigar, the most beautiful I have ever seen. Her family has been growing tobacco for centuries. “My ancestors were canarios, from the Canary Islands,” says Laudeline (66). “We have 16,000 hectares of tobacco. Each year we grow around 450 tonnes. You have no time for recklessness when you grow tobacco. It requires very careful management. That’s the only way to get the very best leaves. My sons and grandsons all work together on the land to make sure the harvest is gathered on time. We operate from sunup to sundown, and then we hope the sun rises early again. It’s a sort of addiction to doing everything perfectly.

You have no time for recklessness when you grow tobacco. It requires very careful management.

Tobacco does grow in other places. For years it was grown in the Netherlands, particularly around Amersfoort. Cuban tobacco is something completely different however, and Cuba’s climate lends itself perfectly to its production. With an average temperature of 25°C and a humidity of 75% the western part of Cuba is the Champagne region for cigars. Add to this the perfect soil quality and voilà: these natural conditions ensure your cigar is of excellent quality and is rich with the best flavours.

What also adds to this quality is that cigar production is under the direct supervision of the Cuban government. Since it wants to protect its stamp of quality, the State ensures every cigar that ends up on the market is an excellent product. Not unusual if you know that last year half a billion Cuban cigars were sold worldwide.

Exclusiveness also adds to this. For years Cuba has had problems with the international export of its products. As a result of the US trade embargo imposed on the country by John F. Kennedy, Americans can forget it if they want to get their hands on a Cuban cigar. And what you can’t have tastes even sweeter, inadvertently giving Cuban cigars more status, as well as those who smoke them.

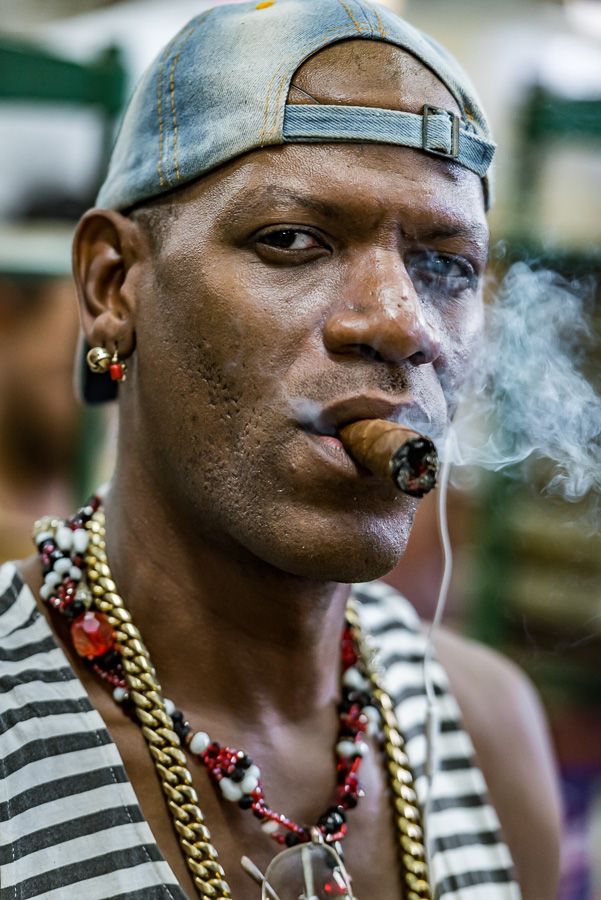

It’s also a beautiful sight, a perfectly rolled Cuban cigar. We are standing in a cigar factory in Havana. On the walls are portraits of the dashing heroes of the revolution: Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. In front of them, the rollers sit behind long tables. Everyone has their own little perch, with a basket of inner and outer leaves. For those of you who don’t know: Cuban cigars are so-called long fillers, meaning all cigars contain whole tobacco leaves, tightly wrapped into one another. This is opposed to short fillers, where only the outer leaf is a whole leaf and inside is ground tobacco. These are considerably cheaper to produce. The rollers work meticulously, music on in the background and some always with a fat cigar in their mouth. Watching them is an art “A good roller rolls around 120 cigars per day. If they produce more they can take them home ” says Nicky Meire from CubaCigar.

Zafado is the art of carefully removing the tobacco leaves after they’ve been taken from the bales.

In another room are women doing the most delicate job of all: separating the tobacco leaves. “It’s called zafado,” says Nicky. “Zafado is the art of carefully removing the tobacco leaves after they’ve been taken from the bales in gavillas (bunches). A delicate task as the leaves must not tear.”

On the terrace of our hotel in Viñales we look at the sunset the evening before we’ll see the sun rise the next morning. We have just enjoyed a dinner of camarones a la criolla (Creole prawns), the coffee is brewing and in front of me is a delightful 7 year-old Havana Club. This calls for a Cuban cigar. I choose a Romeo y Julieta. The waiter slowly and carefully lights the tobacco with a heavy lighter. I take a drag and let the smoke roll around my mouth. It tastes nutty. I slowly blow out and stare off into the distance, the young tobacco plants still gently waving in the breeze.